Controlling pathogens in a dairy processing facility is far from an easy task. In fact, experts will tell you it actually takes a series of intricate steps and considering a multitude of variables to put a successful pathogen control program in place.

The complexities of keeping harmful microorganisms out of products requires such scrutiny that the Innovation Center for US Dairy offers a two-day workshop – and an extensive 100-plus page document that accompanies it – just to cover all the guidelines, principles and details involved.

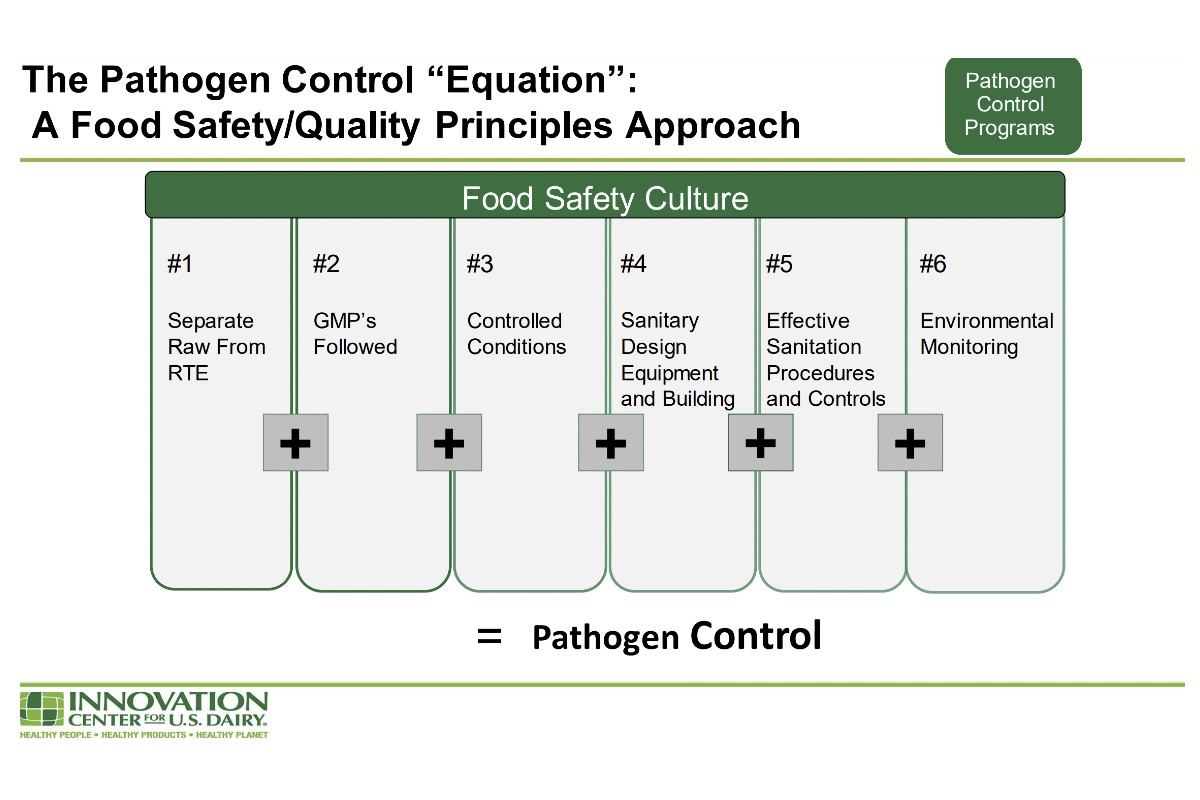

In order to help simplify the numerous actions entailed for dairy processors, the Innovation Center came up with what it calls the pathogen control equation. The food safety and quality approach factors in six principles: separating raw from ready-to-eat, good manufacturing practices, controlled conditions, sanitary facility and equipment design, effective sanitation procedures and controls, and environmental monitoring.

Plus, the equation comes with the overarching idea that establishing a food safety culture to accompany those principles is what makes pathogen control possible, said Chad Galer, vice president of product research and food safety for Dairy Management Inc.

But even those concepts only scratch the surface when it comes to the necessities pertaining to keeping dairy products safe, Galer said.

“It’s not one thing,” he said. “It’s a series of things that creates a program.”

Graphic: Innovation Center for US Dairy

Graphic: Innovation Center for US DairyAdding to the equation

Regulating the flow of people, supplies and air in a dairy processing facility are just a few of the best practices that have become commonplace in the industry. Other proven principles, Galer outlined, involve everything form handwashing and foot control programs to making sure a plant has the right kind of flooring, washable walls and drains that are properly designed.

“These things are important, because if you mess those up at the beginning, you’re just going to spend 30, 40, 60 years fighting those battles – or until you can put capital into fixing them,” Galer warned.

Then there’s infrastructure and proper cleaning to consider, because cleaning improperly can make conditions worse when the right programs aren’t in place, he added. Some of the final steps of the pathogen control equation, Galer said, are making sure all the principles and moving parts are working in unison and verified through testing.

Nevertheless, one of the most difficult aspects of putting an effective system in place, Galer shared, is making sure every person involved in the operation believes in it.

“You’re only as strong as that third shift operator or sanitation person,” Galer said. “The CEO, the head of quality can say all the right things, have great programs, but if (all of the employees) aren’t buying in, all the way down to the people actually executing on the floor, it’s not going to happen – even with the best program. So on top of all these programs, you have to have that food safety culture within your organization to make sure it’s executed at two in the morning when it’s being cleaned.”

Dairy’s inherent obstacles

The dairy industry deals with many of the same pathogen control challenges as other food manufacturers, especially with products that are nutritiously rich for humans, Galer explained. Such products can be fertile ground for pathogens that want to grow.

But the wide array of distinct dairy products, from fluid milk to cheeses, dry dairy powders and more, means the industry must also keep in mind how each product can be affected by pathogens.

Christine Hilbert, senior marketing technical writer for Camarillo, Calif.-based food safety solutions company Hygiena, explained how controlling pathogens can be more challenging with dairy products. For starters, milk itself is complex in its makeup, as a liquid with fats and protein, supporting pathogen growth “really well,” Hilbert said.

“When you collect it from the animal, it’s at the right temperature and it’s not a sterile environment when you’re milking the cow or the goat or the sheep, or whatever you’re getting the milk from,” she explained. “So that’s the risk of introducing pathogens from the start.”

Milk contains “all of the nutrients a bug needs to grow,” Hilbert said, and it can be hard to detect pathogens because of the complexity of the product, which causes interference during assessments.

“So that’s kind of a double whammy against milk.”

Built-in risks come with dry dairy manufacturing, as well. She said powdered dairy is unfavorable to test, because it is one of the most difficult matrices from which to recover pathogens and prevent interference.

“You’re concentrating all those nutrients into a smaller volume that’s very low water content,” Hilbert said, adding that powders, including baby formula, still have those milk fats and proteins. “Nothing’s going to grow, but it’s going to hang out for a very long time, because it’s really happy in that environment.”

To properly examine powders, she said, the product must be reconstituted and tested as quickly as possible, before an organism – if present – has a chance to grow.

Another variable that comes into play for the dairy industry presents itself in fermented products, such as cheese, cottage cheese and yogurt, when a manufacturer is adding good bacteria.

“In theory, those good bacteria should compete and take over and not let that pathogen grow,” Hilbert said.

Even so, she said if a pathogen exists at low levels, it can be even harder to detect in those products, because tests will first pick up the good bacteria. To prevent pathogens in fermented products, Hilbert said rigid processes must be in place and everyone at the facility making those products has to be aware of what they need to do and not do at every step.

Ice cream makers have to be diligent in preventing pathogens such as listeria, Galer noted. Meanwhile, cheese makers, he added, have to deal with varying moisture levels not only in certain kinds of cheeses, but also in the whey that’s separated during the process.

Specifically when dealing with cheeses, Galer said a risk level tolerance difference exists.

“Some cheeses are low moisture, high acid, pretty robust; and then you have some other cheeses that are low acid or more neutral, high moisture – you couldn’t ask for a better media for some of these pathogens,” he said.

Solving problems

To win the battle against pathogens, dairy processors must test at each step of making a product and use indicator testing to monitor plant sanitation and hygiene practices, Hilbert said. Organisms will quickly make it clear when a loss of process control exists, she explained, because they grow under similar conditions, allowing for corrective actions to be taken before a pathogen issue occurs.

Of course, finished product testing is another requirement. But Hilbert pointed out determining the best methods for pathogen detection while also finding tests that provide quick results at a low cost can be a tricky balancing act.

Companies want rapid methods for detecting spore growth, she said, and current methods typically take anywhere form 24 hours to five days, with most taking roughly three days. She said Hygiena offers processes to test for contaminants and detect other organisms.

The company’s Innovate System is a piece of equipment that can run 96 samples at once and test for multiple organisms simultaneously. Hygiena also sells its RapiScreen Dairy kit, which the company made to detect microbial contaminations in a range of dairy products and beverages.

When Galer thinks about facilities that effectively control pathogens, he said their programs tend to possess a “seek and destroy” mentality – “They are actively looking for pathogens in their environment.”

Processors carrying out effective plans systematically check zones throughout a facility, he said, including zones that are furthest from the processing area. Taking preventative measures and corrective actions can eliminate pathogens within a facility.

“If you’re not finding it, you dig deeper,” he added.

It’s in such situations that developing a strong food safety culture pays off. While it’s true that dairy processors want facilities free of pathogens, Galer said plants that effectively execute best practices also include dedicated employees from the top to bottom.

“When you think about seek and destroy, you actually want to reward the people that are out looking,” Galer said. “You want them to dig deeper and find (pathogens) before they get into the food.”