Long before inspection solutions became the focus of his career as the vice president of operations for Arlington, Texas-based FlexXray, Kyle Luker already knew plenty about dairy food safety.

Luker grew up on a dairy farm in Comanche County, Texas, that sold fluid milk to a dairy cooperative. After studying food science at Texas A&M University, he spent 10 of the first 12 years of his professional life making dairy products – cheese for seven years and yogurt for three more – between his time at Schreiber Foods and Dannon.

Now that detecting foreign materials and metals is his area of expertise, Luker considers himself particularly well versed in effective ways to locate contaminants in dairy products.

He said the challenges dairy processors encounter when keeping foreign materials out of their products usually involve metal and rarely come up in fluid products.

“The filtration mechanisms that go on essentially are going to stop almost every foreign material incident that you’re going to get,” Luker said of prevention measures used while processing dairy fluids.

X-ray technology is a solution for locating metals in facilities that produce non-fluid dairy products. But Luker explained metal isn’t the only source of contamination processors run into.

“They’ve got a lot of plastic sources – scrapers, paddles, extruder parts, O-rings, gaskets – that can also become foreign material,” he said. “And unfortunately, there isn’t an inline detection system that’s capable currently of detecting any of those foreign materials at production speeds. So right now, they’re just using an X-ray as the best version of a metal detector that they can find.”

FlexXray’s food inspection services are utilized commonly with dairy products, Luker shared, to find foreign material or inspect product due to missing internal verification from a metal detector or X-ray breaking down. Even though all plants have inline detection, it’s often difficult to use for offline inspection, and FlexXray can provide inspection services for a wide array of scenarios in which post-production inspection is needed.

The company uses medical grade X-ray technology that’s “able to find anything that’s missing,” Luker said. While some companies’ HACCP protocols may run 1.5 to 3.5 millimeters in foreign material sizes for their test spheres, he said FlexXray can capture material as small as 0.8 millimeters. He said the company’s technology can help recover not only metal incidents, but also plastics and ceramics that can otherwise be “virtually impossible” to recover form an inline setting.

While the dairy industry itself is constantly innovating with new products and packaging formats, Luker said from a make process standpoint on the back end, cheese, yogurt, cream cheese and butter all have been manufactured mostly the same way for roughly half a century. So integrating detection technology into operations to further streamline the process oftentimes is difficult.

That’s not to say there has been a lack of technological advancements in foreign material detection. Luker pointed to forays into dual energy X-ray tech as one example of the latest innovations.

“If your maintenance department is willing to invest in better plastics, there are plastics that can be found via X-ray now,” he said.

Petroleum-based plastics are the cheapest kind, and if a dairy plant is constantly cleaning parts and frequently changing out gaskets, Luker gave as an example, using better plastics on $7 gaskets at every pipe juncture probably isn’t appealing when the cheaper variety can be attained for 30-cents apiece.

“But if foreign material is a potential source of recall or rework or scrap or whatever it might be, it can be in your best interest to upgrade your plastics to something that gives you a better opportunity for protection if you do you have an incident,” Luker said.

Investing in the latest foreign material and metal detection technology – and the other costs that may come with taking those steps – could prove beneficial for a company’s image, Luker advised. If dairy processors aren’t willing to invest in the foremost prevention and detection technology for their operations, he added, the prominence of social media also could lead to long-term negative effects.

“Any potential foreign material issue that gets you on Facebook or Instagram or anything else like that, that’s worse than a recall almost now, because that just catches fire and travels so quickly,” he said. “From a recovery standpoint, if you don’t have those options available to you, then you’re playing roulette. And that’s not good for anybody.”

Navigating metal detection

When it comes to detecting metals, dairy processing facilities may have it more difficult than other industries. Robert Slauson, assistant sales manager for Milwaukee-based Advanced Detection Systems, said often multiple factors come into play.

Metal detectors measure conductivity and magnetism, Slauson explained, but the food that travels through them can be conductive, as well. He said because dairy products can contain natural fats, acids and brine, they can be “very conductive.”

Those characteristics have to be taken into account while metal detectors are being set up to deal with specific products at a processing plant. Slauson said a metal detector has to learn the signal generated by a product, so it can recognize it and dismiss it while it is looking for various types of signals that are being picked up.

Challenges may arise in the detection process because of a product’s ingredients, he added.

“You can have small changes – in fractions of a percent different – in certain ingredients from one batch to another and the metal detector sees it very differently. It may look and taste the same to us, but for the metal detector it’s a different ballgame,” Slauson said.

In those instances, he said the machine would need to be retaught, resetting that product for the metal detection process.

“And with dairy you can have tons of different products to manufacture – different types of cheeses, or milks, butters, and that can be in different sizes, different volumes, shapes,” he said of other potential detection obstacles. “All of that comes into play and has an effect and has to be set up or known before going into it.”

Fortunately for dairy processors, technology advancements through the years keep making it easier for a machine to gather information on the product it is inspecting and detect its signal. That has translated to less setup time for companies using metal detection, as well as fewer passes needed to put a product through the detector so it can learn its signals.

One of the other benefits of modern detection options, Slauson added, is the machine’s ability to record and track every event imaginable, form changes in settings, log-ins and passwords, to data a company needs to track.

“You’re no longer having to use a clipboard, paper and pencil to note down your activities with the metal detector,” he said. “It’s all done internally and is easily moved over to something like a spreadsheet of data software.”

The newest metal detectors also are much easier to use than their predecessors. In the past, Slauson said, a plant almost had to have an expert that had been with the company for 20 years and knew the ins and outs of the machinery. Modern detection systems, he added, are nearly self-explanatory, making both training and maintenance upkeep easier.

“Now you just need to be able to understand your way around a touchscreen,” he said, “which most people do.”

Slauson considers upgrading to the most effective detectors available a sound investment, especially when factoring in the costs that come with recalls, including brand damage.

“The whole purpose of a metal detector is to make sure you’re not sending out inedible food to your customers,” he said. “It takes a metal detector finding metal once and preventing a recall once for it to pay for itself.”

Innovations in detection

Photo: Fortress

Photo: Fortress

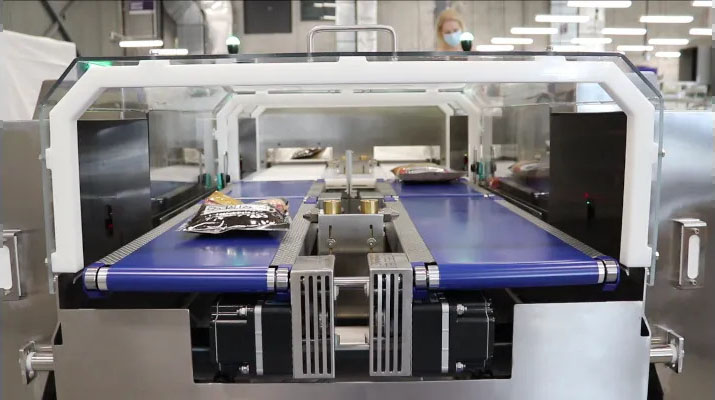

Fortress Technology in Toronto custom manufactures metal detectors to meet specific needs. The company shared that it developed a twin aperture metal detector and dual lane checkweigher for one prominent dairy company.

Regional sales manger Eric Garr said Fortress’ multi-aperture system “was engineered specifically to ensure that there was no trade-off in terms of performance and metal detection sensitivity. One of the key benefits of a twin aperture system is the halving of waste caused by rejects.”

With that setup, a dairy plant can simultaneously run two different product lines, pack sizes or SKUs.

While developing the machinery, Fortress also included air blast nozzles between the two outfeed conveyors, so contaminated product can be removed. At that point, product in question moves into lockable reject bins that are equipped with sensors for confirmation.

“For lighter weight packaged applications like shredded cheese, an air blast reject is the most efficient and has fewer moving parts,” Garr said. “Contaminated products are instantly removed off the conveyor belt without disrupting production.”